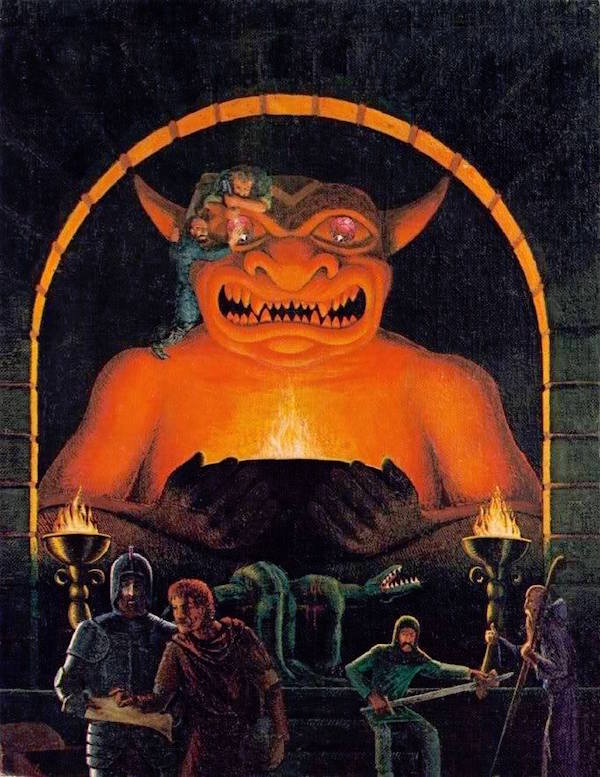

The other day I said offhandedly in the Wandering DM’s discord that I’m halfway inclined to categorize Greyhawk, the first supplement to original Dungeons & Dragons, as a series of mistakes that we’re still paying for. The more I think about it, the more I want to make that case.

Mistake 1: Thieves

The Thief was the first step on the slippery slope of a class for everything, and everything needs a class. Before the Thief, if somebody wanted to perform an action like attempt to pick a pocket or disarm a trap, or even hide in shadows, the Referee would just have to adjudicate it based on assessing the situation and maybe considering things like Dex or armor worn, to taste. After the Thief not only was there a specific mechanic for it, but the Thief’s chances were so low (<50% for almost everything except climbing until about 7th level) that clearly nobody but a Thief should be allowed to attempt it at all. Much ink has been spilled over the years since trying to rationalize or make it workable (e.g. making Thieves skills nigh supernatural, not just hiding but hiding with nothing but a shadow to conceal you). All of that, though, is clearly a band-aid on something that wasn’t originally a wound.

Mistake 2: ATTRIBUTE Inflation

The little brown books (LBB) of original D&D had the Referee (!) rolling up the attributes, called Abilities, for the characters, and then little else there were explicit rules for. The following is pretty much it.

Bonuses and Penalties to Advancement due to Abilities:

(Low score is 3–8; Average is 9–12; High is 13–18)

Prime requisite 15 or more: Add 10% to earned experience

Prime requisite 13 or 14: Add 5% to earned experience

Prime requisite of 9–12: Average, no bonus or penalty

Prime requisite 8 or 7: Minus 10% from earned experience

Prime requisite 6 or less: Minus 20% from earned experience

Constitution 15 or more: Add +1 to each hit die

Constitution 13 or 14: Will withstand adversity

Constitution of 9–12: 60% to 90% chance of survival

Constitution 8 or 7: 40% to 50% chance of survival

Constitution 6 or less: Minus 1 from each hit die*

Dexterity above 12: Fire any missile at +1

Dexterity under 9: Fire any missile at –1

minimum score of 1 on any die

There was guidance in the description of what the abilities mean that hinted ways the Referees might use them, e.g. “Dexterity applies to both manual speed and conjuration. It will indicate the character’s missile ability and speed with actions such as firing first, getting off a spell, etc.” but no formal procedures. There was also some confusing stuff about using your abilities to raise your prime requisite, but it mostly made little difference in play.

So when Greyhawk adds a bunch more explicit rules around abilities, that seems like a welcome change. Finally, this is what the scores in abilities were for! Unfortunately, the way this was done was a mistake and led directly to the current hell of Attribute Inflation where in D&D 5e “Dex-based builds” should be aiming for a 20 in Dex. Where in the LBB, having an 18 Str is no better or worse than a 12 Str unless the Referee deems it important in the situation, starting in Greyhawk a 1st level fighter with 18 STR is better at attacking than a 6th level fighter with 12 STR (same chance to hit, but on average double the damage)… and that’s before the wackiness of the “percentile strength” that gets tacked on once you roll an 18 in STR. The scale is wrong when a lucky roll (or persistence in rolling up new characters) counts for more than months of advancement in play.

If anything Magic-users have it worse with the new intelligence rules. Before Greyhawk a high Int wizard was benefited primarily by leveling up ever-so-slightly faster than an average Int wizard. According to Greyhawk, though, average Int wizards have only a 50-50 shot at knowing any given spell, have a strict maximum on how many spells of a given level they can ever know, and are cut off from learning the highest level spells completely. The exact details don’t matter, though, as much as the fact that now for the first time there’s really an optimal “build” for a character class, and it really matters. You can see this play out in subsequent editions, starting with AD&D where they abandon 3d6 in order in favor of various methods of skewing the numbers towards higher averages (e.g. 4d6 drop lowest, roll 3d6 12 times and take the best 6, etc.) until in 5e you get here, here are your numbers, arrange them.

Mistake 3: Hit Point Inflation

Greyhawk introduced the variable-sized hit die by class “expressly aimed at raising fighters and lowering magic-users with regard to hit points which can be sustained.” Fighters would now get d8, while Magic-users were lowered to d4 (and Thieves came in at d4). Moreover if you used this system all monsters would get d8 hit dice. Since not all weapons were adjusted, the effect was either to draw out combats or funnel everybody into using the weapons that kept parity with the monsters. I’m not sure what problem this was solving (was there anybody who thought too many MUs were surviving to 2nd level?), I think the trend towards both monsters and PCs (except wizards) being ever larger bags of HP was clearly set in motion.

Mistake 4: XP Deflation

Maybe not one of Greyhawk’s biggest sins, but since we’re going through the pages in order… Declaring the original 100 XP per HD ridiculous, Greyhawk adds a lookup table of XP awards that slash them to about a 1/5 to 1/3. Again I’m not sure what problem this solves, although maybe if you’re running games every day of the week anything to slow leveling down is a plus. In theory this tilts the playing field farther towards getting most of your XP from gold, but I believe in practice it just led to more calls for getting XP for other things, or per session and eventually to the current fad of ditching XP completely and leveling up when the GM or module feels it’s appropriate.

MISTAKE 5: THE SINGLE BEST WEAPON

Greyhawk added a number of things that changed how weapons worked in the “Alternative Combat System” (the d20 system that everybody, including Gary, uses). First is variable damage dice per weapon, which I admit I kind of like, but as implemented means that really the only weapons that stay on par with Monster HP are the ones that fighters use. The weapons that do more damage than a 1 handed sword are all flagged as requiring so much space on either side of the wielder that they require the wielder to stand alone in the front line. How Gary reconciled his love of historical polearms with the new requirement that polearm users can never actually form ranks, requiring a minimum of 6′ on either side, I don’t really know. My suspicion is that he only intermittently enforced that rule, if at all. The next widely ignored bit was to-hit bonuses per weapon by AC and different weapon damage against larger-than-man-sized creatures. The interaction between the tables is messy, but the net effect is once again sword is the all-purpose weapon (military pick being better to-hit against the heaviest armor but losing in damage, particularly when it comes to large creatures).

Before Greyhawk all characters would use whatever weapon they liked best (or was most magical) within class restrictions. After Greyhawk, regardless of the specifics, most of which weren’t carried over past AD&D, there was seldom any better weapon than a sword so everybody who can uses that. Heck, one of the most common restriction to relax on Clerics is the one forbidding them from using swords. There have been various attempts, particularly in house rules, to introduce some easier to work with reasons for favoring this or that alternative weapons, such as differentiating between piercing, crushing and slicing damage and making those interact with various monster damage resistances or armor types but frankly they’re all kind of messy. Given the abstract nature of D&D’s combat and Hit Point system the addition of various distinctions between weapons and how they interact with what kind of target seems like yet another mistake. It’s a lot of work to add very little to the decision making process of combat.

Mistake 6: Armor Class Inflation

Or perhaps that’s Deflation, given the descending armor class. For the first time Greyhawk contemplates how magic armor and shields can stack to give you AC even better than plate armor and shield, introducing the dread negative AC, all the way out to AC -8! No, just no. Even when ascending AC became a thing, there were still ACs that went up to 30. 5e eventually tried to rein this in with the concept of “bounded accuracy” but it’s not actually clear they succeeded.

Mistake 7: Monster Attack Inflation

Greyhawk greatly complicated the monsters attacks with a chart of how many attacks and what damage each monster rolled (unfortunately expressed as a range like 2-8 instead of a set of dice to roll, requiring the Ref to back into the roll), most of them becoming very much more dangerous. In the LBB only a handful of the most dangerous monsters like Giants or Hydras ever had more than one attack or did more than 1d6 damage, now more than half the creatures do multiple attacks, more than 1d8 damage, or both. This was the beginning of needing a monster stat block to express what a monster can do, and the beginning of the headaches for the Referee to keep track of all that and use it, culminating in things like The Monsters Know What They’re Doing. Keith Ammann seems like a great guy, and he writes entertainingly, but something has gone off the rails if this kind of thing is really a helpful resource.

MISTAKE 8: Spell Inflation

Greyhawk introduced several of D&D’s most iconic spells like Magic Missile, Web, Magic Mouth, and Explosive Runes. It also introduced entirely new, and imo unnecessary, spell levels: a whole three new levels of MU spells including such game breakers as Reverse Gravity, Mass Charm, Time Stop, and Wish. Clerics get another two whole levels, because Raise the Dead just isn’t miraculous enough. Several of these seem to just exist to excuse Refs putting such effects in the dungeons. Others are, OK, but do you really have 18th level MUs who are going to cast them? What’s going on with your campaign?

On the whole these are relatively harmless, except maybe really blowing out the end-game expectations of what PCs are capable of… and to extent you accept those as goals really putting the emphasis on choosing races and playing characters with scores that can reach those lofty levels. Maybe it upped the temptation to go full Monty Hall just so your players could get there, but the drive to level up was always pretty much the core motivation of the game.

Mistake 9: Infra-Vision

Update: I can’t believe I missed this first time around, but I was just discussing how I removed infra-vision from demi-humans in my games, and I looked it up and found that infra-vision was another thing added in Greyhawk. In the LBB only monsters have infra-vision, and they actually lose it if they become part of a PC party! Not having infra-vision, even for monstrous humanoids like goblins and orcs makes it closer to the way things worked in the Hobbit, reduces the perceived need to have all demi-human parties so as not to worry about light sources, and to makes stealth a more viable option in the dungeon. If the goblin and orcs in the dungeon need light sources it’s no longer the case that the party using a light source will instantly alert all the monsters.

The Rest of the Book

Most of the rest is new treasure, new monsters including several of the most iconic D&D monsters such as Gelatinous Cubes, Umber Hulks, Rust Monsters and Stirges, new traps and some errata. Except maybe the monsters that are really more of a trap and the wild proliferation of cursed items there’s nothing much that stands out as clearly a mistake or a step along a perilous path.

The Prosecution Sums Up

Over all, the biggest effect of Greyhawk taken in toto is to greatly enhance the importance of ability scores, buff fighters, and nerf everyone else, particularly Magic Users. Making MU’s twice as fragile while half as effective at fighting really contributed to the both their perception as not being fun to play (unless you could start at higher levels) and the whole 15-minute workday phenomenon that even 5e is still struggling to counteract. In retrospect I see Greyhawk as being in some ways a product of the so-called “death spiral of improvements” that besets many fields of endeavor as new works cater more and more to jaded experts, lessening if not ruining much of their initial charm and approachability for novices. When you’re running a campaign for many players, nearly every day of the week, lots of new high-end toys for them to play with and more procedures that offer minor variation even if somewhat more baroque and cumbersome can seem especially attractive, while making things increasingly frustrating and difficult for low-level characters or reducing the variety of viable characters seems like a minor price to pay. At this point in an established campaign, you might hardly have anybody playing 1st through 3rd level characters as even when characters die you’re letting them start at a higher level or inherit the funds and equipment of the original character or they’re catching up in a few session from their split of loot in higher level adventures.

So what would I actually use from Greyhawk? Honestly I’m not sure. If I were to run a specifically OD&D game, and not some kind of B/X hybrid, I probably would pull in most of the new spells but not the new spell levels, all of the monsters and treasure. Beyond that I’m really not sure any of it is worth it. There’s a strong temptation to do something explicit for high or low ability scores and to provide some incentives to use different weapons, but I think I would really try to rely more on just applying more Referee’s discretion to work things out.